Corporate Courts: The Case of Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS)

- Jinane Ejjed

- Aug 11, 2025

- 8 min read

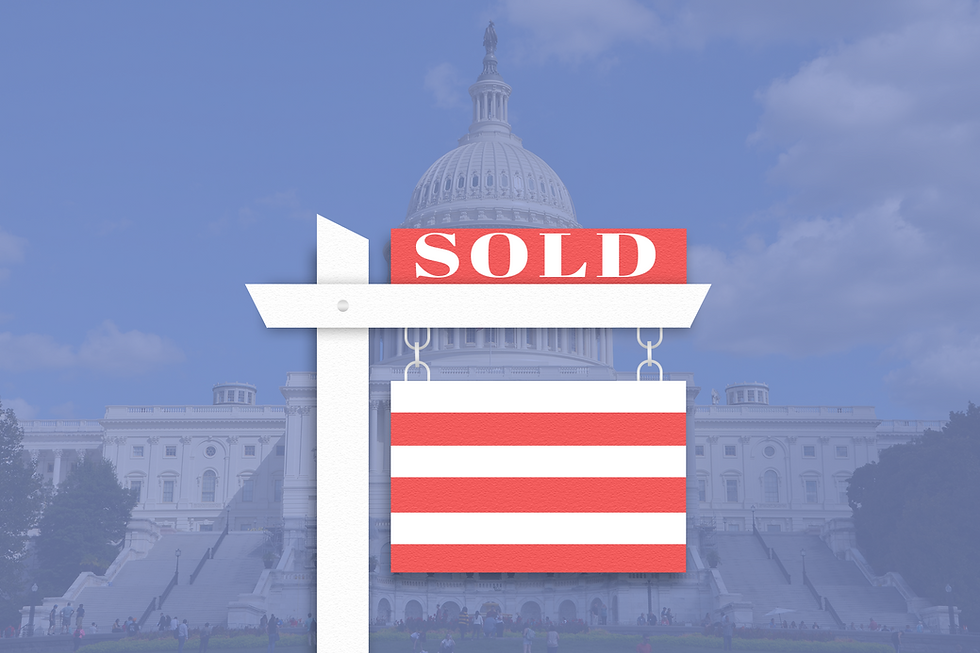

The hidden court system allowing corporations to sue countries—and reshape global politics in the process.

When Cecilia Malmström, the former EU Commissioner for Trade, proposed replacing the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism with an Investment Court System (ICS), backlash from neoconservative think tanks came swiftly. The origins of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) can be traced to early 20th-century U.S. bilateral treaties—specifically, the Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation treaties of the 1930s and 1940s. These agreements introduced the principle that investment disputes arising between a foreign investor and a host state should be resolved through neutral arbitration, rather than through the domestic courts of either party or through traditional diplomatic channels. ISDS thus established a formal mechanism through which private corporations could bring claims against states, typically in cases of expropriation or policies perceived as equivalent to expropriation.

While the U.S. government has historically relied on domestic legal systems to resolve such disputes, many corporations have expressed distrust of host country courts, especially in politically volatile or adversarial contexts. For instance, Venezuela once maintained amicable relations with foreign investors but later adopted hostile policies, illustrating the appeal of ISDS as a tool to provide legal certainty amidst shifting political landscapes.

However, ISDS has become increasingly controversial due to its structural bias in favor of multinational corporations. Although ISDS provisions are typically codified in public treaties, the arbitration proceedings themselves are opaque, conducted in private without public oversight. Such secrecy, combined with the expansive interpretation of what constitutes a violation of investor rights, has enabled corporations to challenge domestic regulations—particularly those related to environmental protection, public health, and labor rights. In practice, regulatory measures intended to serve the public interest can be reframed as barriers to investment, thereby positioning regulation as an obstacle to investor protection. Consequently, ISDS functions as a bill of rights for multinational corporations, limiting the ability of states to regulate in the public interest and entrenching a legal regime upheld by neoliberal ideology. These sets of legal rules, created within a realm of individualized, market-based competition, reflect the preferred governing principle of neoliberalism for shaping human action in all areas of life—both at the individual and collective level—by subordinating democratic decision-making to market logic and insulating economic governance from public accountability.

States and international institutions crafted ISDS mechanisms to protect transnational capital from the uncertainties of domestic politics, embedding investor rights in treaty law to bypass national courts and democratic accountability. States and international institutions did not stumble upon Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS); they engineered it as a deliberate tool to protect transnational capital from the unpredictability of democratic governance. These mechanisms were not created to ensure justice but to embed investor rights in treaty law—above and beyond national courts, domestic laws, and citizen accountability. ISDS is not simply a technical instrument of arbitration; it is a cornerstone of neoliberalism’s transformation of the state itself—from a locus of democratic sovereignty into an enforcer of global market discipline. Far from neutral, ISDS tribunals crystallize a worldview in which “the market” is not an abstract force but, as Seth Rockman argues, “a euphemism for actual economic actors (people) and institutions (law and culture) that shape how economic power is exerted and experienced.” State power, in this sense, is never absent—it is mobilized to insulate capital from the very public it affects. Juridical insulation is operationalized through a set of near-universal treaty provisions. Chief among them are national treatment and most-favoured nation clauses, which prohibit states from favoring domestic firms or less privileged foreign investors. Such clauses, alongside sweeping protections against expropriation and restrictions on capital flows, establish a legal firewall against democratic policy shifts.

As early as 1957, Hermann Josef Abs, Nazi banker under the Third Reich and postwar architect of global finance, envisioned this framework as a “Magna Carta for capitalism,” a charter not of rights for people, but for capital. Quinn Slobodian has shown that neoliberal architects did not seek to dismantle state power, but to redeploy it, to “encase” markets within international legal orders that preclude interference from national democracies. ISDS thus represents not the erosion of sovereignty but its repurposing: a project to embed capitalist imperatives in law, hardening investor privilege into the infrastructure of global governance.

Multinational corporations routinely deploy Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms to coerce governments into withdrawing or weakening public interest regulations, fostering a pervasive regulatory chill that erodes democratic governance over health, labor, and environmental policies. As climate concerns have intensified, this backlash against ISDS has become more pronounced: after decades of supporting ISDS as essential protections for investors and promoters of foreign investment, several European countries have grown skeptical of its climate implications and consequently withdrawn from the Energy Charter Treaty, a key multilateral framework for cross-border energy cooperation. In 2009, Swedish energy giant Vattenfall challenged Germany’s environmental regulations in a $1.9 billion investor-state dispute under the Energy Charter Treaty. The case arose after Hamburg authorities, responding to public pressure and climate concerns, imposed stricter environmental conditions on a coal plant permit to protect the Elbe River. Vattenfall argued that these conditions amounted to indirect expropriation and violated its right to “fair and equitable treatment.”

Despite democratic legitimacy and domestic legal recourse supporting the regulations, Germany capitulated in a secretive 2010 settlement that revoked the environmental safeguards, allowing the plant to operate while obscuring the financial burden borne by taxpayers. This case illustrates how ISDS privileges investor rights over public welfare, pressuring states to abandon climate policies vital to global sustainability. Similarly, In 1997, the U.S.-based Ethyl Corporation launched a NAFTA investor-state dispute against Canada, challenging its ban on MMT—a gasoline additive containing manganese, a known neurotoxin. Canadian lawmakers had enacted the ban due to health and environmental concerns, asserting provincial jurisdiction over environmental regulation.

Despite MMT being banned in reformulated gasoline by the U.S. EPA and largely unused globally, Ethyl claimed the regulation constituted an “indirect expropriation” under NAFTA. After a NAFTA tribunal upheld the company’s standing, Canada settled the case, paying Ethyl $13 million, reversing the ban, and publicly declaring MMT safe. While ISDS provisions function to disempower states and erode the integrity of national regulatory frameworks, findings from the Columbia Center on Sustainable Development reveal a troubling pattern wherein ISDS is deployed to contest domestic judicial decisions—even absent any substantiated judicial bias or misconduct. The enormous arbitration costs incurred by states further divert critical resources away from judicial reforms that could strengthen equitable access to justice, illustrating how ISDS benefits a narrow set of powerful actors at the expense of broader societal interests.

Collectively, these cases and dynamics underscore ISDS’s role as a manifestation of capitalism’s historically unique and lawlike expansion, what William Sewell describes as a transformative social logic that renders its institutions seemingly inevitable and immutable. From territorial conquest to manipulated trade relations and coerced financial dependency, capitalist systems have consistently extended control through mechanisms that concentrate power while displacing democratic accountability. ISDS is part of this legacy: its historically unique lawlike power and social dynamics make it increasingly difficult to grasp, let alone oppose, entrenching a system in which investor privilege becomes both a norm and an obstacle to dismantle. In this light, the persistence of ISDS reflects not simply a legal regime, but a deeper structure of global power—one that fortifies the dominance of transnational capital by foreclosing the political capacity of states to govern in the public interest.

Furthermore, ISDS empowers corporations to initiate legal action against states without offering reciprocal rights to those states or ensuring transparency in the adjudication process. This asymmetry entrenches a fundamentally unequal system in which investor power is shielded from democratic scrutiny and accountability. As Karl Polanyi argues, the self-regulating market was not a spontaneous development but rather a product of deliberate state intervention. He further posits that attempts to organize society around market principles inevitably provoke counter-movements, as individuals and institutions resist the social dislocation wrought by unchecked economic liberalism. ISDS mechanisms, in this light, function as defensive fortifications against precisely such democratic resistance: insulating transnational capital from the counter-movements Polanyi predicts. In 2012, Veolia Propreté, a French multinational corporation, initiated an investor-state dispute against Egypt, seeking at least $110 million in compensation following the government’s decision to raise the minimum wage in the wake of the 2011 revolution. The wage increase was part of broader efforts to dismantle remnants of Hosni Mubarak’s corrupt, military-backed regime and respond to long-standing demands for economic justice. Veolia argued that Egypt’s labor law reforms, particularly the wage increase, violated provisions of the France-Egypt Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) by adversely impacting its 15-year waste management contract in Alexandria. Specifically, the company claimed Egypt failed to shield it from the financial implications of these policy changes, thereby breaching its obligation to provide fair and equitable treatment. Although the arbitration tribunal ultimately ruled in 2018 that Egypt had not violated the BIT and had not engaged in expropriation, the state was still required to cover a portion of the costly arbitration proceedings. Veolia Propreté v. Arab Republic of Egypt exemplifies how, even in legal “victory,” states incur significant financial burdens, costs that ultimately fall on citizens.

By insulating investors from the very social and political forces that challenge the unchecked expansion of market logic, ISDS also suppresses the democratic agency necessary to contest the social consequences of global capitalism.

The investment-treaty regime emerged not only in response to decolonization and the subsequent globalization of the international order, but to adapt to a world where citizenship, democracy, liberal capitalism, and moderate redistribution were all vested in the nation-state. Building on Ogle’s insight that offshore “archipelago capitalism” is not an aberration but a deliberate and integral component of capitalism’s evolution, ISDS represents a carefully constructed mechanism designed by global elites and state actors to shield capital from democratic accountability. Functioning as a bill of rights for multinational corporations, ISDS exemplifies capitalism’s broader transformation of the state into an enforcer of market power by embedding investor protections in international law to circumvent domestic democratic processes. Rather than functioning as neutral instruments of economic governance, ISDS tribunals concretize and perpetuate a vision of “the market” as a system governed by powerful actors—corporations, legal institutions, and transnational trade frameworks—who deploy these mechanisms to discipline states, suppress regulatory autonomy, and entrench capital’s dominance over collective political will.

Bibliography

Agreement Between the Government of the French Republic and the Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Reciprocal Encouragement and Protection of Investments. Signed December 22, 1974. Entered into force October 1, 1975. Electronic Database of Investment Treaties (EDIT). https://edit.wti.org/document/show/044a57d4-03f1-4dcb-93b9-4a6137935d16.

Block, Fred. “Introduction: Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Times.” In The Great Transformation, 2001 edition.

Bonnitcha, Jonathan, Lauge N. Skovgaard Poulsen, and Michael Waibel. The Political Economy of the Investment Treaty Regime. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

European Parliamentary Research Service. Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS). Briefing, January 2015. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2015/545736/EPRS_BRI(2015)545736_EN.pdf.

Energy Charter. European Commission. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/international-cooperation/international-organisations-and-initiatives/energy-charter_en.

Korn, David, Thibault Denamiel, and William Alan Reinsch. Investor-State Dispute Settlement: A Key Feature of Trade Policy in Response to Climate Challenges. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), February 15, 2022. https://www.csis.org/analysis/investor-state-dispute-settlement-key-feature-trade-policy-response-climate-challenges.

Neoliberalism Education Project. “Introduction to Neoliberalism.” University of Georgia. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://neolib.uga.edu/introduction-to-neoliberalism.

Ogle, Vanessa. Archipelago Capitalism: Tax Havens, Offshore Money, and the State, 1950s-1970s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Rockman, Seth. “What Makes the History of Capitalism Newsworthy?” Journal of the Early Republic 34, no. 3 (2014): 82–109.

Rocha, Maria, Martin Dietrich Brauch, and Tehtena Mebratu-Tsegaye. “Advocates Say ISDS Is Necessary Because Domestic Courts Are ‘Inadequate,’ But Claims and Decisions Don’t Reveal Systemic Failings.” Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (blog), November 29, 2021. https://ccsi.columbia.edu/news/advocates-say-isds-necessary-because-domestic-courts-are-inadequate-claims-and-decisions-dont.

Slobodian, Quinn. Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Sewell Jr., William H. “The Capitalist Epoch.” Presidential Address of the Social Science History Association, 2012. Social Science History 38, nos. 1 & 2 (Spring/Summer 2014): 1–24.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). “Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of | Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator.” Investment Policy Hub. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement/country/228/venezuela-bolivarian-republic-of/investor.

Van Harten, Gus. Investment Treaty Arbitration and Public Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

van der Merwe, Ben. “How Two Businessmen Wrote the Rules of Globalisation.” New Statesman, April 2, 2021. https://www.newstatesman.com/business/2021/04/how-two-businessmen-wrote-rules-globalisation.

Vattenfall AB, Vattenfall Europe AG, and Vattenfall Europe Generation AG & Co. KG. Request for Arbitration. ICSID Case No. ARB/09/6. March 30, 2009. https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0889.pdf.

Veolia Propreté v. Arab Republic of Egypt. ICSID Case No. ARB/12/15. Award. May 25, 2018. https://www.italaw.com/cases/documents/10617.

This is a great piece of writing. Keep up the outstanding work and maybe sometime you will be a writer of a prestigious college or news source.